|

home

advanced |

Figuring Figuration by

Deborah Knight VI Elevated and Bathetic Tropes In his book, In-Yer-Face Theatre, Aleks Sierz speaks of Steven Berkoff as one of the pioneers of this theatre of the nineties… along with the tragic drama of ancient Greece, Jacobean tragedy, and gothic fantasy; all, by the bye, theatrical periods that Berkoff himself revisited at the beginning of his career as a theatrical director and playwright with his adaptations of Aeschylus and Sophocles, Shakespeare and Poe. What, then, could in-yer-face theatre possibly be? Sierz defines it in the following way:

What

could be the point of it?

Antonin Artaud, inventor of the ‘Theatre of Cruelty’, commented on the psychology-obsessed theatre of his day in his book The Theatre and its Double in the following way:

It would seem his British disciple of the seventies took this very passage as a direct challenge, for like it or not, Berkoff’s themes can practically always be reduced to whether or not his characters are having, to use the French theorist’s words, a ‘good f*ck’, and that preoccupation can be seen to lie at the very heart of his social critique. In my introduction I spoke of the roller coaster effect of Berkoff’s theatrical language, in which one feels constantly transported from the highest of highs to the lowest of lows and back. As I will demonstrate, the move from elevation to bathos [Ref 2-01] or from euphemism to dysphemism is more often than not carried out in order to uncover the sublimation of sexual desire as the causal base of various ‘civilized’ practices, showing these latter to be nothing other than tropes, or distortions, of the libido. These range from the closest to the farthest, most camouflaged forms of sublimating sexual desire: from channelling it into an excessive preoccupation with certain related parts of the anatomy to transforming it into, say, a partiality for tea. In every case, the individual’s sense of his or her own identity or the identity of the Other is intimately linked to the form his or her sublimation has taken. Lyotard writes:

6.1 The

sublimation of the libido into ‘civilized’

tropes

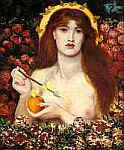

And yet, although he admits in the first paragraph that the ‘useful organs’ are only a sign of desire, he appears to forget this initial figuration in the second paragraph when viewing the ‘sign of love’ as being ‘displaced from the pistils and stamen’ (or genitals), thereby inadvertently furnishing us with an immediate example. It is not they, but the workings of the libido that he is clearly intending to place at the centre of the picture. There is never any initial ‘displacement’ made from the physical ‘useful organs,’ as the human mind instinctively attributes the workings of love or the libido to the metaphysical, and thus initially figuratively evokes the corolla or person. In this respect the flower metaphor of Berkoff’s story “Daddy” that we looked at in the last chapter is more pertinently employed in that it does succeed in evoking the mechanisms of desire. As we saw, the ‘strange flower’, the ‘unclassified plant’ in Cyril’s ‘psyche’ figuratively approximates his essential self far more closely than the resolutely heterosexual public image his reputation as a ‘womanizer’ (36) secures him. However, Cyril’s achievement of this truer sense of ‘self’ is only made possible by eliminating any subjective reciprocity with the Other. When he does involuntarily become aware of the Other, the wording of the story is sufficiently ambiguous to leave the reader wondering if it really was his father he saw, or whether his vision was simply distorted by projection. As we have seen, Cyril himself wonders if fear did not change the identity of a perfect ‘stranger’ into that of the paternal figure who, by dint of his professional identity as law enforcer in a heterosexual world, is the symbolic guardian of his public persona. Bataille’s evocation of desire takes into account the other, and yet his self-contradictory argument reveals him to contemplate the object of desire through the synecdoche of the physical, reminding me of Lyotard’s criticism of Merleau-Ponty’s effort to deconstruct the subjectivity of the self in order to see the subject not as an entity but as ‘an open field of compossibilities within the flesh’, which is ‘founded upon resemblances within an originary differentiation’ (Aesthetics of Excess 60). Lyotard saw his theory as using the body to dissimulate the libido, saying: ‘To accept the body as the location of events is to endorse the defensive deplacement, the vast rationalization produced by the platonic-Christian tradition with the intent of concealing desire’ (63). At first glance, it would seem that Bataille is doing the opposite by viewing the sexual organs as the site of displacement for the figuration of desire. But is he? Perhaps Berkoff’s famous ‘c*nt’ speech that composes scene 17 of East, the first original play he ever staged, could better answer that question. The play’s two randy young East Ender machos have been talking about the best places to pull ‘quality c*nt’ (East 38) and Mike proffers the following argument against Les’s claim that the best ‘c*nt’ used to come from ‘Billingsgate’ (38):

Although Mike attempts to depersonalize the girls that arouse him by concentrating on the appearance of their genitalia in much the same way as Bataille revealed himself to imagine these as laying at the source of the ‘love’ women receive, it is only the subjectivity of his description that comes anywhere near conveying desire. Mike would have Les believe in his complete detachment by reducing the metaphysical, that would engage his subjectivity, to the merely corporeal. Any aspiration to gain complete mastery of the Other can only be consolidated by treating this latter as a wholly interchangeable entity. However, despite himself, the very same flights of fantasy that evoke his desire also personify each ‘c*nt’, paradoxically enlarging the vision of each organ to take in attributes of the very owners he had tried to dispense with. This peculiarity reminds me both of C.S. Pierce’s words quoted in The Semiotics of the Theatre and Drama, ‘semiosis involves “a co-operation of three subjects, such as a sign, its object and its interpretant”’ (25, my emphasis) and Weiss’ words in Aesthetics of Excess, ‘the erotic is founded upon the relation between passion as pure libido and the spirit as displacement and repression of the libido’ (69). With each identity-conferring interpretation, Mike’s auto-figuration is also made manifest, inaugurating the very inter-subjectivity that permits entry into gregarious existence. Control of the symbolic by means of its elimination in the literal would deny openness to difference, to the Other, leaving nothing to be exchanged and developed through interpretation. As the figurative movement in Mike’s speech links the bathetic trope of the genitals to the more elevated trope of personification, it could be seen as a form of metaphorical paradigm of the vertical connection between the libidinal source and social identity. The last lines of the passage represent the more upward reaches of this figurative displacement, as concern for literal meaning (semiosis) gives way to the predominantly mimetic figures of lyricism:

Although Mike clearly senses he has let himself go in the first part of the sentence and attempts to retrieve greater metaphoric precision in the second, the subjectivity of his disfiguration has already revealed a sensitivity his carefully controlled habitual persona would rather die than admit to. Having said that, the main drive of the above passage is that of dire male chauvinism, of the sort that traditionally denies woman identity. We will return to this point in the following chapter, but for the time being it is interesting to note that his first audiences back in 1975 found this scene hard to watch [Ref 2-03]. Berkoff, himself, put both his and their embarrassment down to the taboo-power society had endowed the word ‘c*nt’ with, explaining that he had to say it over and over again until it had been ‘pummeled to death’ (In-Yer-Face 26) and the shock had worn off ‘by a process of overkill’ (26) to render it acceptable. I am inclined to think it was not the repetition, but the change in his manner of enacting the scene that altered its reception. Perhaps the explanation below as to why certain words become taboo comes nearer hitting the mark:

Aleks Sierz also asserts that although certain subjects might be bearable when one reads about them in private they will suddenly seem electrifying when we hear about them in public. (7) This is equally true of things we are in the habit of hearing every day, such as the common occurrence in England of women being referred to as ‘c*nts’. Keir Elam speaks of the way Bogatyrev and his colleagues drew attention to the fact that:

Brecht describes the same phenomenon as the Russian formalist notion of Ostranenie (defamiliarization or ‘making strange’) when defining his alienation effect, the Verfremdunseffekt:

I find it intriguing that Berkoff admits it was only through endowing each ‘c*nt’ with character and acting it out that he made the scene easier for both himself and the audience to get through [Ref 2-04]. Could it be the horrendous spectacle of quotidian male chauvinism, rather than any so-called power in the word itself, that causes the embarrassment and awkwardness? I would suspect so. And, despite the widespread belief that we can no longer be shocked today, I also imagine that to be the reason for the producers ‘coyly’ (26) renaming the scene ‘the pudenda speech’ (26) in the programme of Berkoff’s 1999 West End revival of the play. Although the word ‘pudenda’ still refers us to the sexual parts of the female anatomy (even if it remains politely before the door), it simply does not conjure up the disquieting image of the foul-mouthed women-haters its unfortunate ‘synonym’ does. By giving each ‘c*nt’ ‘character’, Mike himself is subtly transformed into a feeling, sentient being… hardly the stuff of chauvinists. In fact, in the video of the 1999 version of East, Mike is shown enacting Berkoff’s original mime of pushing himself first into and then out of a giant invisible vagina. Over and above symbolically suggesting he is thereby being re-invested with social identity, this ‘rebirth’ also metaphorically restores to woman the signifying capacity that Freudian and Lacanian accounts of identity have traditionally excluded her from. Before Mike enters and exits the vagina he says the words from the quotation above, thereby turning what Freud and Lacan termed an ‘empty signifier’ into the basis from which he creates meaning. This could be seen to bear up Julia Kristeva’s refutation of her male predecessors sexist argument. By instilling the uterus with the same sort of magical symbolic power they gave to the ‘signifying’ penis, she sees women not as stranded outside of meaning as they would have it, but as symbolizing the very space and possibility of meaning by representing the wordless pre-Oedipal Unconscious, the biological preliminary to the signifying subject’s entrance into language, consciousness and Symbolic (patriarchal) order. In support of Julia Kristeva’s argument, it is noteworthy that the greater part of Berkoff’s male characters only seem to find significance to their lives upon entering womankind, where they recover the ‘familiar feeling of home’ (Gross Intrusion: “False God” 100). In his one-man show, Graft: Tales of an Actor, George Dillon graphically illustrates Berkoff’s story about Harry’s dependence on the once common afternoon leisure activity of tea-dancing for getting closer to the source of his cravings, by showing himself to be tugged from the groin across the ‘womb-like… velvety…’ ‘subterranean cavern’ (“Resting” 74) by an invisible force emanating from the women of his fancy. He scarcely needs to say the words: ‘sperm-filled men pursued egg-filled ladies in a furious dance and maybe one or more lucky spermatozoa would eventually penetrate’ (74). The story foregrounds the very oddity of a civilized ‘ritual’ that, in the narrator’s words, ‘gives you permission to put your arm around a complete stranger and feel their body, hold their hand in yours, smell their odour, brush their thighs and then leave, like it’s a test for both of you’ (81). Again, Berkoff’s narrative is hardly necessary to support Dillon’s mimed rendition of the following passage from the story: ‘A dance ended and a couple who seemed entwined as if joined at the hip like Siamese twins, parted suddenly, each exploding off in different directions with no music to glue them together any more, or justify embracing a complete stranger’ (76). Of course, when an activity such as this brings the underlying instincts that civilization has vetoed so close to the surface, it is the women above all who have learnt to keep up the more finely-tuned precautionary show of indifference, more often than not going so far as genuinely to believe in it:

The bathetic passages of this story that liken this civilized custom to courting rituals to be found in nature - ‘a sniffing out in a wide-open prairie under a hot sun when two animals slowly circle each other, sniffing, examining, sensing by the highly-tuned mechanism whether the smell is strong, good, and suggests virility and health, for it has to be of equal value’ (81) - restore a closer semiotic connection between the figure of tea-dancing and the libido, while the female dancers’ obstinate refusal to confer awareness upon their actions turns the actual practice into an elevated, hence predominantly mimetic, figure of their primal desires. The prescriptive forces of the patriarchy that invented such a state of affairs have not been so successful with the men’s ability to deny the source of their pleasure in the custom. Harry, like the creatures of the Savannah, feels

However, the supreme self-confidence that the tactful ambiguity of the last sentence implicitly indicates is, unfortunately, not the protagonist’s. Harry’s faith in the reciprocal nature of hormonal signals does not come to back him up in his hour of need, however much he tells himself he is the same league as the beautiful Jewess he has been watching with ‘almost indecent longing’ (77). He imagines ‘whisking’ her off onto the dance floor, ‘her lips facing his, her eyes his eyes, nose to nose, smile to smile and breathing in each other’s breath’ (82) and her sniffing him as ‘potential genetic material’ (82), but, as he walks across the floor towards her to ask her to dance, he is already forecasting how her rejection will momentarily drain his ‘most precious life’ (83) of all meaning: ‘FOR A SECOND YOU ARE IN LIMBO SINCE YOU ARE EITHER ON THE THRESHOLD OF CREATING A THOUSAND NEW GENERATIONS OR YOU ARE WITHOUT PURPOSE’ (83). Thus, he is destined for failure from the start, for ‘like the conditioned Pavlovian dog, poor Harry approaches the object of his hunger with the accompanying fear of receiving an electric shock, which does not make for secreting those sexual odours that women are supposed to find so attractive’ (84). ‘How could she possibly know the layer upon layer of crumbled hopes that formed the foundation of his request? Upon the ancient ruins of disappointment were the foundations of his new church, but now it was… “Care for a dance?”’ (85). Although she smiles at him after ‘making that split-second assessment that girls have to make’ (85), she denies him that particular dance because she wants to rest. Harry interprets the rejection as proof that she does not consider his ‘material’ ‘suitable to mix her chromosomes with’ (83) and, convinced that every other man in the room is watching him to see what he will do with ‘the egg slowly sliding down [his] face’ (83), walks out. Unlike the creatures of the wild, Harry doubts the reliability of his senses rather than acknowledge his rational understanding that what prevents his modern ‘Goddess of Fertility’ (84) from reciprocating Nature’s call is her adherence to the social niceties. On his way home he thinks ‘F*ck her’, ‘trying by demeaning his Goddess to demystify her’ (86) in a way not so very far removed from the debasing epithets Mike used in East that made him such a boor. If the request of a ‘dance’ remained both in keeping with the energy that provoked it and the refined values of a sexually-repressive society, the nature of the ‘new church’ (or trope) being erected from the ‘ancient ruins’ of the, to all intents and purposes, guaranteed sexual disappointments of Harry’s afternoon pastime does not seem to augur well for the loving mutual admiration between the sexes that Plato so naively imagined when innovating his concept of sexless lovers that civilization has been so eager to embrace.

Rather than be brought to heel by society’s conventions like the conditioned Pavlovian dog that Harry has become in “Resting”, here it is ‘Man’ who calls for ‘Woman’ to be brought to heel. The above passage casts an elucidating light on what would be traditionally perceived as an ignominious treatment of ‘Woman’ in the next:

Is he

not, in fact, rather forcibly reminding her she is first

and foremost an animal, even though frustration distorts

his delivery, making it appear to be a classical case of

perverse and chauvinistic dominance? Despite the explicitness of passages like this, the overall impression I get in reading this play is that it must be enacted rather like Gay Sweatshop’s As Time Goes By of 1979, which ‘features a scene in which two men make love simply by using words, without touching or looking at each other, symbolizing a love that is forbidden’ (In-Yer-Face 26). However, the sexual politics that intercede continually in the small talk that metaphorically substitutes the sex act in Berkoff’s 1983 play may well show wariness to be even more ubiquitous in heterosexual courting than in the homosexual version, as paranoia is galvanized within the intimate circle of the couple’s relationship by the very Other, rather than adopted by both partners as a defensive strategy against the rest of the world. The metaphors Berkoff’s protagonists use are not simple projections of their lascivious hopes upon the sea waves. In fact they hint far more insistently at all the fears society’s customs have taught them to anticipate from the illicit, or legal, satisfaction of their desires. Hence, one of the very first moves in ‘Man’ and ‘Woman’s’ courting is the inaugurating of a contractual type of relationship through indirectly alerting each other to the temperamental qualities they would wish for in the opposite sex, by conferring the merits of their predilection upon the waves:

They go on to allude, each in his or her way, to the economically-based customs of a patriarchal society that exchanges woman’s favours for financial security:

They hint at their respective fears: ‘Woman’, perhaps, of rape, ‘Man’of fatherhood,

evoke their incompatible attitudes towards the sex act, ‘Woman’ onomatopoeically expressing a preference for foreplay, ‘Man’ for getting on with the job in hand

and pronounce a mutual, if differently experienced, relief when he does get it over with:

They finish by hinting at perennial irritation with the seduction strategies they are chained to and that demand that all advances originate with the man. His efforts are either seen to be overly aggressive or excessively sycophantic by ‘Woman’:

When ‘Woman’ keeps telling him to go away, his response implicitly negates his supposed readiness to comply with her wishes by evoking his true state of sexual excitement, highlighting once again the very oddity of a civilization that obliges its inhabitants to express themselves in antiphrasis:

While the gang members of West call their leader ‘Royal Mike’ (51), the Sylv of both that play and East calls him her ‘royal Mick’ (East 11) which, at first glance, elevates him in the same way his ‘mates’ do, but in fact subtly insults him as the meaning of the second word breaks down in rhyming slang to ‘prick’ [Ref 2-06] with the word ‘royal’ being used in its English capacity as an intensifier. His own appellation for himself in the passage above comes nearer to the libido-identity link, as his idiosyncratic use of the idiom ‘personality-plus’ in context, ‘I could mash thee into and ooze with my personality-plus once turned on’, is obviously meant to house under the same lexical roof his self-image, his penis and his libido, with the latter being seen to be evoked in the ellipsis appearing between ‘into’ and ‘ooze’. The fact that Sylv not only, to all intents and purposes, calls Mike a ‘prick’, but also tries to emasculate him, shows her to be attempting to deprive him of identity in much the same way he used on the girls at the Lyceum. If it could be argued that he at least was not so perverse as to de-sex them, sexing a woman is generally regarded to be every bit as debasing as ‘castrating’ a man. It would be nice to think this is simply because of the appropriated form a woman’s sexuality so often takes, as suggested in Sylv’s method of packaging herself and advertising her contents in a marketing strategy that unequivocally targets the sexual fantasies of men: ‘pink tipped, tight box, plumbing perfect – switches on and off to the right touch….’ (16). In the play these words are accompanied by the actress’ crisp sharp illustrative mime movements, making her look for all the world like a doll, while her description of herself as ‘a raincoat’s fantasy’ (16) shows her inability to see herself as a sexual being otherwise than through a man’s eyes, making her sexuality, and hence her identity, his dominium. Her only possibility of retaliation is instinctively to deprecate the male sexuality that has thus enslaved her. In turn, Mike simply fields the insult by referring her back to her social status as merchandize that only finds value by meeting the prerequisites of the demand, while his use of Jacobean English as the vehicle for one of Shakespeare’s favourite metaphors, the economy, to get the message across, figuratively takes on all the prescriptive power of canonical literature.

Whereas Sylv and her like do not have the wherewithal to remember to enforce the part of the transaction in which they financially profit from being ‘goods’ up for sale, the upper class Helen is shown to be a savant manipulator of her market value, even succeeding in dispensing with her part of the bargain, ‘giving in’ to the sex act, altogether. Or, perhaps I should say, almost, for she still caters to her man’s sexual proclivities by relying on her not inconsiderable talent for the ‘telling of a tale’. In fact, the only scene in which she is shown to take part in sex is one illustrating the narrative of a sexual adventure she recounts to the guests of a dinner party she has thrown. The story tells of her orally pleasuring a young man, the breakfast waiter of the hotel she is staying in, while ‘the beast’ (19) she has accompanied on holiday sleeps ‘snoring in his lair’ (19) in bed beside her. While her dinner guests are engrossed by the story, her present lover is shown to be held in rapturous thrall; probably because of the way the story topples the aristocrat from the pinnacle of social hierarchy, even placing him below ‘his’ woman’s sexual servitude to a servant. The scene depicting the couple’s fully clothed enactment of the hunting woman’s relationship to her horse renders Steve’s desire for subordination quite explicit, while the hold Helen maintains over him is made clear in the way her masterly narratives cater to his preference for reported or simulated sex. Helen’s beautifully seductive but ephemeral smile is shown in the film to be Steve’s heart-gladdening reward, while its constant solidifying into relentless discontent is the whiplash which keeps his wallet, if not his flies, open. The ‘decadence’ here is not of the joyous Bacchanal sort that is supposed to have characterized that of the Roman empire, but of the type that the script depicts as arising from the corporal punishments and gay initiations of all-boys British boarding schools, the impervious smug complacency that is inherited along with admittance into the world’s most prestigious club of hooligans, the House of Lords, and the perverse effects of the women’s financial dependence upon their men being hardly improved by both sexes’ severe upper class sexual repression. Although the lads of East may brag of their sexual conquests they are obviously not as frequent as they would have each other believe, for the street fights they engage in are shown to be another form of outlet for their exuberant youthful libidos. When Mike challenges Les to a fight for leering at Sylv, Les’ flirtatious response is that of a girl being propositioned. His awareness of his coquettishness is evinced in the words he chooses to narrate his own dialogue [Ref 2-07] and is again confirmed in his later description of the welcome alleviation street fighting brings to the mind-numbing dullness and hopelessness of his East Ender life: ‘Oh! Ho! I gushed. You fancied me round the back with boots and chains and knives behind the super cinema’ (8).

The voyeuristic ‘yobs’, who, like customers at a brothel witnessing a young girl’s deflowering, ‘leer’ and ‘lust [Ref 2-10] for blood to flow, blithely leave them for dead, pleased with the night’s show but fearing the retribution of the law. The combatants pick themselves and all their ‘bits’ ‘off the deck’, fall ‘into each other’s arms’ ‘flashing a quirky red soaked grin’ at their ‘daft caper’ (10), and help each other to the nearest hospital, urging one another to grip onto life. Mike describes them as being ‘in love’ (10) by the time they stumble into ‘Charing Cross’ (10) while Les’ use of both the literal and metaphorical imports of the idiom ‘to paint the town red’ shows his satisfaction with his new-found ‘mate’ (10) and the shedding of his ‘virginal’ blood. He has had a festive night out: ‘I only had a pint or two of rosy red in my tired veins myself… the rest I used to paint the town with…’ (10).

Whereas Harry had only one desire, and that was to ‘whisk’ his ‘egg-filled’ Jewess onto the dance floor, the sailors of Sink the Belgrano! are being sent to the Falklands to break eggs [Ref 2-11] , or in other words kill ‘Argies’, for the ‘Spanish omelette’ Scratcher is hell bent on aping in her 20th century version of enforcing British colonialism in Latin America. As they wend their way below the ocean waves, the sailors aboard ‘The Conqueror’ sing with pride of their ‘egg-filled’ submarine:

The wording and punctuation of the second line evokes their cheerful comradely acceptation of a fate that will most probably lead to the ‘laying out’ of their corpses, rather than a future of ‘getting laid’ the comma between ‘will’ and ‘mate’ puts paid to. The whole passage sardonically emphasizes the curious way in which metaphors that employ fornication as their vehicle have come to conjure up images of violence and hatred, deprecation and death. Remaining on the food trope, the motherly Mum of Massage presents a ‘menu’ to the furtive customers of the massage parlour where she works in order to elevate and thus divorce from the physical the spoken transactions that have to be made when ministering to their bodies’ needs. They speak of the men’s desires as if they were pizza toppings:

A ‘City Gent’ even appears to go so far as to confuse Mum not only with a Cocktail waitress but with the drink she would serve, the second part of his ‘order’ calling to mind stock phrases for the transmitting of beverage-serving preferences such as ‘and make it on the rocks’: ‘give me a massage, Sherry, if that’s you name and make it topless now as well’ (191). A waitress at work, Mum is likewise a waitress at home, serving up an unending supply of tea to her babyish coalminer-striker husband, who, as yet, remains blissfully unaware of the true nature of her extra-domestic activities:

The ‘mate’ in the penultimate line is an obvious indication that far from fulfilling the primary sense of the word for each other, this childless couple have contented themselves with a platonic relationship: their bed being every bit as cold as the tea, and probably for the same reason. In the light of subsequent revelations, the same line suggests that this living ‘hell’ is far from hot, but cold, whilst the ‘heaven’ Dad eventually catches a glimpse of is most definitely sizzling. His addiction to tea is soon shown to be not only, as the above passage indicates, an adult version of the baby pacifier, but also a powerful deadener of the sexual urges, despite his sharing the common view of it as a potent elixir. One day he goes for a stroll in the countryside, lies down for a nap and awakens upon his ‘green and silken bed’ (208) to the sound of distant church bells striking four and the realization that he will miss England’s teatime ‘forgetting’ of their ‘fears’ (208). Instead, this unaccustomed wandering from the straight and narrow abruptly awakens his long repressed libido, very nearly turning him into a child molester, as we shall see later. Although he is ‘saved’ by ‘relieving’ himself in one of the local saunas, he quickly recovers his opinion of himself as an upright, honest citizen. Despite drawing the audience into collusion with him earlier in the play by telling them about his secret visits to this sauna, his boyish acting all holier than thou in front of Mum when she comes in to serve him his tea and toast is paradoxically a better indication of his belief in his virtue than his ‘roguish’ confidences would lead one to suppose. The way in which his rhyming Cockney slang likens these staples of the English diet to the Eucharist bears witness to his engrained sense of self-righteousness:

The dramatic irony is, of course, that the audience already knows the very service he has availed himself of for the ‘best part of his sting’ is the same as the one his wife offers in another establishment on the high street. This theatrical manoeuvre subtly places the audience in cahoots with her, thereby showing them to plug for the catering to of physical needs rather than for the opposing sanctimonious call for sexual abstinence. In fact it is not really Jesus that is evoked in Dad’s allusion to anointing his bread with perfumed marmalade, but rather to the unknown woman who poured costly oils over Jesus’ head shortly before his crucifixion, bringing to mind the way in which mum ‘anoints’ her customers’ penises with 'oil that’s precious and perfumed in musk’ (191) before dispatching them back to the martyred lives they lead in the real world. Rather than the pastor who watches over the virtue of his flock, Mum fulfils a reparatory function as ‘the shepherdess who tends the sheep / and milks the cows, for that is how it seems / squeeze out the nectar and the pain / I’ll rent my hand and voice / my subtle touch to their world-weary aching ends of flesh’ (191). And the work is gruelling. It is ironic that when Mum tells us that Dad’s ‘once almighty hard on has lately bit the dust’ (195) is ‘no small relief to a girl who is engaged all day in giving same at work called ‘on the game’ / tho’ game it hardly is / more like a slog to get through the assembly line of dirty dogs’ (195) she has no idea how her curious idea of leisure is contributing to another woman’s hard labour elsewhere. Proud of the service she gives not only at work but also at home as family breadwinner and ‘mother’ to her husband, Mum views the middle class wives as the really iniquitous harlots who ‘milk’ [Ref 2-14] their men in the more common sense of the idiom despite the fact that her own altruism revolves around economically based exchanges that either serve her financial or self-righteous interests:

While she prides herself on restoring the ‘gallant men of England’ sufficiently to enable them to return to

City Gent simply sees her as the less expensive of two evils:

The rhyme on ‘feed’ and ‘greed’ lays the accent on the Christian sense of guilt that keeps him yoked to his role as family money slave. It is not woman as Mike of East would have it who keeps the economy going, but man, who, through shackling the free expression of his libido to the restrictive confines of the nuclear family his patriarchal society invented, has turned woman into an item of financial exchange either through wedlock or prostitution. Ironically juxtaposed with Dad’s resulting near rape of two schoolgirls and his subsequent visit to the sauna is Mum’s self-satisfied description of how her work keeps the families of her customers safe from harm by providing precautionary measures against the more pernicious consequences of such a system:

And what of the women? The onomatopoeia in the following passage from Greek drives the message home that their frustration and discontent with such an arrangement is every bit as perilous as the men’s:

The next two passages are just as graphic in their efforts to illustrate the extremely adverse effects of a society that attempts to quell the visceral through indulging the cerebral:

The ‘Double speed mime of joyful domestic eating scene to music’ [Ref 2-15] (198) that Mum and Dad perform directly after having confided in the audience about their illicit extra-domestic pursuits is highly reminiscent of a similar scene in East. There, Mike, Sylv and Les punctuate Dad’s ignorant fascist ravings at the supper table with frozen tableaux of their otherwise real-time mime of insouciant cocky enjoyment of their meal. By displaying the teenagers’ caricature of the conscience-freeing image the middle-class nurture of the ‘happy go-lucky Cockney’ along with the frighteningly real opposing one of Dad, the disparity between the two is pithily illustrated. The Times theatre critic Patrick Marmion expresses it thus: ‘Are Cockneys really buoyant, bouncy chappies? Cockneys are violent, bigoted, acquisitive, ignorant, sex-obsessed, self-hating – but otherwise, one supposes, all right.’ We could well pose similar questions and answers in relation to the double speed mime of Massage that satirically depicts the highly mediatized category of the ‘happy family’ everyone wants to belong to. One cannot help thinking of the a-sexual character of the family that is evoked in the following passage in direct connection with the religious wars it has inadvertently caused through engendering the different faiths of Christendom. As he walks through the ‘war’-torn streets of the London of the late 70’s on the way to seeking his fortune, the protagonist of Greek, Eddy, comments on the I.R.A. pub bombings,

and imagines the cause of ‘Paddy’s’ propensity for war to lie in his inability to make satisfactory love to his wife:

If obscenity is not intrinsic to the word ‘c*nt’ or to the part of the female anatomy it labels, but rather to the person who uses it, no more does it inhere in the word ‘f*ck’, but rather in the violence that replaces the absence of the act it connotes. By the same token, blasphemy is not shown to lie in the evocation of the holy family in the preceding passage, but in the sexual repression Christianity has advocated and the hostilities it has provoked. When Command sends their Mark-8 torpedoes to blow up the Argentinean battleship in Sink the Belgrano! the only repentant Sailor on board the submarine unthinkingly evokes the very Holy Trinity that has played such a great part in such a state of affairs, when he prays: ‘God… let them not feel any pain…! [Ref 2-16] Oh Jesus Christ…’ (182).

And as Maggot Scratcher’s projection of her well-repressed libido into a desire for a ‘Spanish omelette’ demonstrates, woman’s parallel self-deception can go so far as to provoke wars. Below, her recipe for this dish from Sink the Belgrano! is placed in juxtaposition with another contributed by Mum of Massage that indicates the nature of the primary sources in the food chain that compose the ingredients that finish up in Scratcher’s omelette. Mum’s recipe seems at first to be addressed to the Scot she is massaging, but the way in which it echoes Scratcher’s reveal it to be an inter-textual, or inter-play, response to the iron lady.

Hanging’s no answer to the plague madam’ (112) the Eddy of Greek imagines responding to the sort of drastic proposals Scratcher could envisage for putting England back on its feet, ‘you’d be hanging every day / I’m human like us all’ (112).

One may well wince over the language of many of Berkoff’s bathetic passages, but the sublime simplicity of perhaps the most bathetic of them all, Eddy’s response to his future wife’s equally straightforward sexual invitation, highlights the extreme factitiousness of the elevated language that precedes it. However, it must be said that even the caricatured representation of this literary register still maintains its credentials as the most suitable vehicle at mankind’s disposal for the communication of positive libidinous feeling:

These two go on to form Berkoff’s most sexually satisfied and amorous pair, probably delivering his most beautiful lyrical passages in spite of the fact that they turn out to be a modern version of the original Oedipal couple. Whereas the ellipsis that figures Mike’s libido also mimics his haste by appearing between two verbs, the particularly aggressive verb ‘mash’ and the verbal metonym of his orgasm, ‘ooze’ [Ref 2-19], Eddy’s appears as the culmination to a long ode to womankind, and most particularly to the woman of his heart whose ‘love-soaked parts’ (127) that ‘want’ him are the essential prerequisite that comes well before the end:

When Eddy discovers that his wife is in fact his mother, he flees his home to walk through the ‘masturbating-shop’ (123) –lined High Streets of the city, plagued long before any sin of his. Of course, he cannot help comparing the happiness he shares with his ‘desirable lovely succulent and honey-filled wife’ (137) favourably to the ‘dead souls’ he sees about him who, along with their ‘real’ wives, are ‘plastered forever in casts of drab compromise’ (137). He sits in a café and lets his memory pore through ‘every page’ of the ‘great holy bible of magic events’ (138) of their life together, and realizes that far from running from her he should be telling her:

Earlier in the play he ironically comments that the ‘old hoary myth’ his adopted parents used to tell him before he left home 'subtitled could be called the story of a mother f*cker / a tale of kiddiwinks to send them mad to bed and cringe at shadows in the night, and in their later years to bung good gelt to shrinks in Harley Street’ (128). By viewing the telling of the Oedipus myth as engendering the very need for the Freudian psychotherapy that was invented in order to resolve the resulting ‘complex’, the play ironically illustrates the self-construction that characterizes the socializing decrees or metanarratives of civilization, and the way in which they cooperatively prop each other up. We will go on to look at how Berkoff’s plays portray literature’s contribution to the preservation of perhaps society’s most uncivilized prescriptive habit in the next chapter, but for the time being it is interesting to note that if the macho Mike of East supports the way in which society has denigrated female sexuality in order to enchain woman to her ‘virtue’ by treating Sylv as if she were a whore and her vagina as a ‘Pandora’s box’ (17), the visionary Eddy calls the ‘hoary’ story that renders sinful his joyful marriage a ‘right box’ [Ref 2-21] (Greek 137). Whereas Mike contradicts his deprecation of Sylv’s sexuality by admitting in the very same breath that he has to ‘tease’ it open with carefully chosen words which naturally elevate her in both of their esteem [Ref 2-22], Eddy wishes the Pandora’s box of social taboo had never have been opened.

And

on that note falls the play’s final

‘blackout’. Like Mike, Eddy lovingly climbs in

and out of woman’s vagina, but, unlike the former,

he also lovingly etches her libido along with his into

his language, by figuring the bathetic trope of her

physical ‘ellipsis’ as the metaphorical site of

the fulfilment and reciprocation of his desire. By

figuring Western civilization’s most honoured icon

of virtue, the mother, as indisputably sexual, the play

restores to woman, any woman, her right to a healthy

sexuality of her own. And by portraying an incestuous

couple, society’s gravest taboo, as the happiest of

them all, Berkoff plainly indicates that in his world, as

in Deleuze’s and Guattari’s, it is ‘the

law’ that should be ‘inscribed in a

pornographic book’ (Aesthetics of Excess 44),

for it is society’s sweeping prohibitions that

commit the real crimes, in committing crimes against

nature.

© Deborah Knight 2001 |