|

home

advanced |

Creating

the "Berkovian" Aesthetic Chapter IV Ensemble and Chorus

Unity within a company is one of the most rewarding elements of the theatre process for Berkoff. Although tension inevitably surfaces due to Berkoff’s rigorous rehearsal demands and passion for his art, he considers these tensions a unifying force. It is for this reason Berkoff tries to work with the same actors as much as possible; once a company has been through the creative "wars" together, he believes a mutual respect has been earned amongst the participants. In a 1978 interview with Theatre magazine, Berkoff told Christine Eccles “I never work with anyone I’ve never worked with before . . . After the strangeness, the difficulties, the rows, you stick with the people you know” (133). In a 1992 interview, Berkoff told Midweek’s William Cook, “The key to my ensemble work lies in the intensity between the actors and the way we marshal their choreographic skills” (10). He often subdivides a large cast of characters into a smaller unit that serves as a chorus whose physicality shapes the entire production. The physical unity of an ensemble is an important aspect of Berkoff’s work because, he hopes, a deeper sense of trust within the group will emerge. His search for camaraderie is one of the reasons he embraces the familial structure of theatre:

Theatrically, this “family for misfits” is exemplified in a couple of forms. It is unfair to judge his chorus as merely an extension of his need for friendship because his one-man shows also use choral elements. For the purposes of this analysis, I will divide Berkoff’s choruses into two categories: large ensemble productions in which the chorus actors primarily create psychological and physical environments while playing multiple roles (The Trial, Agamemnon, Hamlet, Sink the Belgrano!, Coriolanus, Salomé, and Richard II) and productions with smaller casts whose actors play defined characters and take part in the chorus (Metamorphosis, East, West, and Greek). The major function of these choruses is to comment, illustrate, and clarify other characters' actions. Established theatre companies did not provide the close-knit relationships Berkoff required, as his stint with the Royal Court demonstrated, so he became adamant that he have the resources (primarily time) in order to create ensembles founded upon trust and experimentation. The casts of the earliest productions, the Kafka adaptations (1969) through Hamlet (1979), were especially close-knit and formed The London Theatre Group. [Ref 4-1] He based his rehearsals upon improvisation and movement exercises he learned from Le Coq and Chagrin which are meant to create a strong, trusting ensemble. As he free-lanced for outside companies, he sometimes got off to rocky starts as early as the auditions. He conducted performance workshops to cast the chorus, but, as in the case of Coriolanus (1989), he had to cast “as you might cast a chorus line in a musical. I didn’t know their names and couldn’t be subtle about it” (Coriolanus in Deutschland 21). Early in his career, before commercial time restraints forced him to rush, he led extensive auditions:

Though it was meant to build a cohesive ensemble from the beginning, Berkoff’s Darwinian philosophy is intimidating to those actors not used to a process-oriented audition. If a cast or crew member complains, Berkoff generally takes it personally and has no qualms about asserting his authority, as he did while directing Coriolanus in Münich in 1991. He looks at first sheepish and then malevolent since the arsehole feels that he is indispensable and nobody gets sacked in Germany. Most of what he says is garbled and untrue -- lies that “we’re all confused” or “unhappy,” which is a crock of shit. I say “get out,” since I have had enough of his whining. “You are bad for this company,” I add, “and we don’t need you, you are corrupt” -- in the sense that he was corrupting all around him. (Coriolanus in Deutschland 89-90) During Berkoff’s rehearsals for his 1995 production of Coriolanus in England, which premiered at the West Yorks Playhouse in Leeds before transferring to the Mermaid Theatre in London, he had similar difficulties. Berkoff prefers to fire an actor over employing those he deems destructive, negative or inferior -- assuring that his cast will remain committed to the production. His “us vs. them” philosophy motivates some actors to thrive, but others are inevitably weeded out:

Berkoff enjoys such opportunities to “slap down” the established British theatre companies, especially the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal National Theatre, as he holds them personally responsible for what he considers to be the poor state of British theatre. Berkoff’s wrath is not confined to the actors; everyone involved in a production is subject to his scorn, even if he fragments the entire company. Those who survive his criticism are welcomed as part of his “gang,” while those who do not make the grade are shunned. The late Joseph Papp, artistic director of the New York Shakespeare Festival, described such an experience which occurred during rehearsals for Coriolanus in 1989:

Although there was friction between Berkoff, Walken (who played Coriolanus) and the designers, Berkoff remained dedicated to the chorus, describing them as “a unit of modern streetwise actors who fused together as a team and then, emboldened with their power and the impression they were making, flew into every scene like greyhounds” (Coriolanus in Deutschland 20). In this sense, he treats the chorus as one complete element of the production, and once they have gelled, is a separate, yet integrated component of a company along with designers, administration, musicians, and lead actors. The notion of “streetwise actors” has particular appeal to Berkoff considering his pride in his own working-class, gang-related background. Berkoff’s playwriting certainly has always commented on British politics and class. Likewise, he believes that his concept of ensemble is a critique of the British class system.

Berkoff’s issue with the class-system lends itself to a socialist philosophy of ensemble -- everyone will contribute equally to the whole. There are no “spear-carriers;” instead, he tries to use every actor to their fullest potential. Through the chorus, Berkoff takes advantage of the core of the theatrical event: the actor.

He began work on future productions independently and then he recruited other cast members -- many of whom he had previously worked with. He began his rehearsals for Hamlet (1979) by himself, then added two more actors. He then enrolled more actors until they were a finished ensemble of ten actors (I am Hamlet ix; Eccles 133). Berkoff claims he remained invested in an ensemble approach: “I wanted no central star around which other satellites revolved [. . . .] We had to be in it together, part of the fabric of the play. I, as Hamlet, in fact wanted to see what they were doing at any given moment” (I am Hamlet 3). That being said, Berkoff has often cast himself in substantial roles, such as in Agamemnon, Macbeth, Salomé, and Coriolanus. Occasionally, Berkoff will play a smaller role, though he has never only participated in the chorus. In The Trial he played Titorelli and confides: “I only have to be on for twelve minutes, but those twelve minutes leave me in a state of exhaustion as if I sprinted a mile,” providing Berkoff with, “great satisfaction in that I am not so responsible for the acting [. . .]” (Free Association 376-377). As Berkoff grew as a director, so did his reputation for having a dictatorial style. For early large cast productions like The Trial (1970) and Agamemnon (1973), Berkoff relied on group input and improvisation. By 1979, Berkoff had been directing regularly for ten years and The London Theatre Group began drifting away from their self-described label of “AN EXPERIMENTAL FRINGE GROUP” [Berkoff’s emphasis]. He stopped requiring movement exercises before every rehearsal, fearing they would tire the cast. He does have some regrets in the change, believing that the exercises would have “UNLOCKED MANY DOORS FOR US” [Berkoff’s emphasis] (I am Hamlet 80). Later he became more result oriented, partially due to commercial time restraints; a heavier load of commitments to various projects; and a stronger, more complete vision of his desired finished product.

The Trial, Berkoff’s first large-cast production, is a good jumping-off point to trace the evolution of his use of chorus and ensemble. Berkoff entered rehearsals with a general idea for the final product but no specific movements, blocking, or choreography. In this play the chorus is a specific unit, or, a character unto itself. This chorus alternately compliments and contrasts with the lead characters. In his treatise “Three Theatre Manifestos” (1978), Berkoff describes how he developed his mise-en-scène early in his career, noting that: “readings and improvisational exercises in movement and mime became the starting point of a production” (Gambit 8). Berkoff echoes this stance in Free Association, which he wrote thirteen years after “Manifestos”: “I am the kind of person who works out a concept. I’m not like those fortunate directors who say, ‘I’ll plot the play in three days and then we’ll fill in the detail’” (52). The rehearsals for The Trial became a process whereby the cast read the novel page by page, and improvised as they went along (121). He believes that if a rehearsal process is too structured it will also be restrictive:

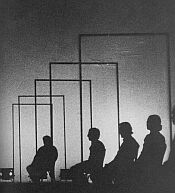

After a five week rehearsal period, Berkoff workshopped The Trial for six weeks in London at the Oval House before it received its official première at the Round House three years later. In the completed production most of the cast remained on stage throughout the play to create the physical world seen through Joseph K’s eyes. They worked out a scheme with a set of door frames, inspired by the line in the novel: “Before the door stands the doorkeeper.

The use of actors in Berkoff’s plays can be separated into three major categories: first there are lead actors playing only their individual roles, including the performer portraying Agamemnon, Hamlet, Coriolanus, Salomé, Richard II and Bolingbroke in their respective shows. Next are actors playing substantial roles and participating in the chorus, including Gertrude and Polonius in Hamlet; and Mr. and Mrs. Samsa in Metamorphosis, etc. Finally, there are actors confined to the chorus such as the sailors of Sink the Belgrano!, the partygoers of Salomé, and the soldiers of Coriolanus. In Hamlet (1979), Berkoff used a cast of ten to create Elsinore, a characteristically active world. In I am Hamlet (1989), Berkoff explained the functions of the chorus, made up of the entire cast sans Berkoff in the title role:

This description is generally true although, according to Berkoff, there were some exceptions. Of Wolf Kahler, who played Claudius, Berkoff says: "his 'resting' or watching positions as chorus were never those of the casual watcher. His were careful, apposite, and instinctively right for the scene" (129). As Hamlet, Berkoff was usually the focus, though at times he too tried to dissolve into the chorus: "Although I am sitting, the drumbeat continues for me. I am, if you like, 'offstage' . . . and only my actor's body waits" (131). Berkoff’s quest to assemble a close-knit ensemble led him to an all black cast for the 1984 revival of Agamemnon. He “felt that the American blacks were fitter, stronger, more physically alert and better-voiced than their white competitors.” Returning to a recurring theme he observed, “the blacks were a community and had a camaraderie that I thought would make a great ‘chorus’” (152). He was pleased with the outcome, finding this production to be amongst his best. He is aware of ethnic generalizations associated with his casting choice: “I will plead guilty to any charges that may be laid, in that I was looking for athleticism, fervour, community spirit for the Chorus and strong voices. They had all of these qualities in ‘spades’ [Ref 4-2] and it was one of the most enjoyable experiences of my directing life” (77). In Sink the Belgrano! (1986) -- Berkoff’s most political play -- he used a large chorus more so than any production since Hamlet (1979). The cast of nine played all the roles, which included farmers, yobs, sailors, and members of Parliament. Beside the group of actors serving as a chorus, there is one specific actor designated in the cast list as “chorus.” He serves as a narrator, bridging locations and describing actions while the group illustrated, through mime, torpedoes being fired, explosions, and other effects. This device in Sink the Belgrano! -- one actor consistently speaking for the group -- is unique in Berkoff's canon. The only other script to use this device is his 2000 adaptation of Sophocles' Oedipus Rex. Coriolanus (1989) continued the focus on the chorus as the heart of a large-cast production. Berkoff’s description of the chorus for Coriolanus emphasizes the ensemble, but in this production he centers on the human characters they will portray, not of the objects they will become: My “chorus” for Coriolanus will be all men, a combination of soldiers, rebels, citizens, servants and messengers. A team will evolve like a corps de ballet and that is what it shall be, as it was in the New York production, the heart and centre of the play. They will be all people at all times and nearly always be on stage. They will be the two armies of Coriolanus and Aufidius. (19) After directing Coriolanus in New York (1989) and Münich (1991), he tackled the title role himself in London (1995). Critics sarcastically commented that Berkoff would not take over a smaller role, and drew focus from the ensemble. The Times' Jeremy Kingston seizes upon the point, smugly commenting in his review: The posters bill the play as “directed by and featuring Steven Berkoff.” This brings a moment of concern: “featuring” is usual film parlance when a commanding actor is brought in to play a minor role. Would Berkoff be appearing as one of the tribunes, or the hungry plebeian whom Menenius calls, in his parable of the body, “the great toe?” (Features n. pag.) Robin Thornber latches on to a similar theme, calling Coriolanus: “a one-man show with a large cast of extras” (Guardian T5). This type of criticism began during Hamlet (1979) and has grown ever since. City Limits critic Carl Miller charges that Berkoff stilted his production of Salomé (1989) and intimidated the cast: “He [Berkoff] deliberately unbalances the play. Everyone allows Herod to get away with things because they are scared of him, and it seems to have been the same with Steve” (quoted in Cook. n. pag.). This type of criticism, bordering on the personal, would hound the director for the remainder of his career. Berkoff’s attempt to integrate himself into the ensemble is impossible. Because he directs, produces, writes and/or acts in his plays, his individual name, and style, are inextricably bound to the production. This issue is further complicated by his choice to play lead characters. For example, because both Hamlet and Coriolanus revolve around their title characters, the plays’ structure dictate that Berkoff cannot dissolve into the chorus. The rest of the ensemble can become a chorus because it is counterpoint to Berkoff’s personality and character. He is aware of the perils associated with wearing too many hats. Berkoff writes of the “fear all those of us who direct and play the principal have, that we have to earn respect on two levels simultaneously” (Free Association 297). Once other theatre companies began to regularly hire Berkoff to direct, he didn’t consistently work with the same core of actors. Berkoff now travelled the globe directing shows and working with new actors or, in some cases, recasting shows as their runs progressed. For example, in 1982 Berkoff directed Greek in Los Angeles, for which he was awarded five Los Angeles Critics Circle Awards. He later remounted it in New York to poor reviews. Two years later he remounted the production, with a cast altered from the original production and was awarded a California Arts Council grant to tour the production throughout California. He addressed his dislike for this system in a 1984 interview with Anne Marie Welsh of The San Diego Union Tribune, when he remarked,

Although Berkoff claims that he prefers to stick with a single cast to fully explore a play, his reaction to recasting Salomé challenged this claim. In fact, he was accused of stealing his own production of Salomé from the Gate Theatre in Dublin and recasting it for what became a successful run at the Royal National Theatre in London. Apparently his sense of loyalty to the Irish ensemble faded, insisting he “could have performed this work with any group of actors [. . .] The company was a good company, but not the Moscow Arts, and the success I must modestly say was due to the production, which I had conceived down to the last note,” mainly because, “It was not created, as some shows are, by mutual improvisation and discussion plus the natural creative flow of mutual discovery” (Free Association 360). In other interviews, Berkoff gave the Irish cast more credit, saying "I admired and with whom I had an excellent and affectionate working experience" (quoted in The Stage and Television Today 2). These problems compounded themselves when critics again accused Berkoff of narcissistic theatre. City Limits’ Carl Miller reviewed Salomé observing: “the rest of the cast seem of no more consequence than set dressing” (quoted in Midweek 10). In City Limits, George Dillon -- a long time Berkoff associate -- answered Miller’s review in a letter to the editor: Berkoff’s directional methods stems from his being an actor himself and his wish to see actors performing at the height of their ability. He does not, as some directors do, manipulate his actors until they are confused and intimidated and utterly dependent on the director’s word [. . . .] He constantly invites actors to contribute ideas, many of which he takes up, so that at times it can seem like direction by committee. (n. pag.) In his 1991 article "Naturalism, like Smoking, is Bad for Your Health," Kenneth Rea of The Times cites a variation on this idea: Actors find Berkoff the director at once demanding, uncompromising and liberating. "He doesn't create characters in the usual way," says Paul Bentall who is working with him for the first time [in The Trial]. "He's got the whole thing in his head and it's a complete structure that he gives you. He shows you, very brilliantly and very quickly. But because it's his baby, he cannot bear things to be not as he sees them. It's practically physically painful for him. Once you can get on his level, you can start doing things and you have real freedom. (Features n. pag.) Berkoff addressed this issue in my 1998 interview in Liverpool. When asked how much freedom an actor has within a Berkoff production, the director answered:

The plays discussed so far have relatively large casts, allowing Berkoff to create a chorus within the ensemble. Interwoven through his career are smaller cast shows in which he continued to use a chorus, though all of the chorus members also play identifiable characters. In Metamorphosis, East, Greek, and West the chorus are made up of family members. Metamorphosis (1969) is the earliest example of a small cast play in which he creates a chorus, comprised of Gregor’s parents (Mr. and Mrs. Samsa) and sister, Greta. They are a unit who act and react together, as a mechanical representation of the Samsas’ mundane existence. In the stage directions to his published adaptation of Metamorphosis (1981), Berkoff consistently refers to the family as a group: “The mime of FAMILY eating, looking up, wondering where GREGOR is, in unison linked as a chorus” (83); “Image -- FAMILY face downstage reversing the scene, i.e., audiences see their faces, fear, anger from GREGOR’s point of view” (90); “The FAMILY retreat slowly” (91); “They [family] are crouched behind their stools as if watching him in the distance” (93). However, each character also has an individual persona: Mrs. Samsa has a “sad face” and a “pained heart of angst,” Mr. Samsa “strolls boldly” as a “lower middle-class tradesman,” and Greta is “an amiable being.” After their individual entrances, Berkoff directs them, as a group, to “take on the movement of an insect by moving their arms to a particular rhythm,” which, “has the effect of an insect’s leg movements” (79). Each family member has at least one scene with Gregor to establish their personal relationship: Greta is compassionate, Mr. Samsa is contemptuous (consistent with most father-figures in Berkoff’s work), and Mrs. Samsa is sadly maternal. The family, or chorus, remains on stage for the entire play. There are also two additional actors in the play that portray the chief clerk and the lodger (sometimes double-cast) who function as outsiders to the Samsa household and are not specifically a part of the choral unit. In contrast to the opening stage directions that create the rhythm and image of a bug, Berkoff ends the play with the following stage directions: “Taking their [Mrs. Samsa and Greta’s] hands, they hold him [Mr. Samsa] as if they had no other means of life -- attempting somehow to kindle a new life force through the current of their bodies” (121). Whereas the family/chorus started the play as a unit that created rhythm, mood, and the grotesque image of an insect, Berkoff ends the play by suggesting catharsis: “MR. and MRS. SAMSA, sensing each other’s thoughts, turn to look at GRETA -- she releases their hands and stretches -- their smiles confirm their thoughts are in harmony” as Mr. Samsa delivers the final line: “The crocuses will just be coming out” (121). The dénouement establishes a world of harmony and flowers for the family/chorus. Although the role of Gregor has the potential to be a star vehicle, the play could exist without him appearing on stage. If the chorus functioned completely as narrator (which they do at times), the story could be conveyed without Gregor’s presence. In a 1999 article for The Independent, Berkoff explained before he developed his mime-based portrayal of Gregor, he considered "several versions where we could only see the beetle via the family" ("My Metamorphosis" 9). As the action is not focused on the possibility of reversing his transformation to human form, the family/chorus quickly resign themselves to the idea it will never occur. Berkoff writes the play through the family’s perspective, chronicling their transformation as well as Gregor’s. Currant notes that although Gregor “does not really dominate the play -- his family’s attitudes are perhaps the principal focus of the play [. . .]” (175). Currant goes on to say that Gregor is the most well-rounded character because the family “tend to repeat the same facets of themselves when appearing" in various scenes. While there is some truth in Currant’s assertion that the family are unchanged, I think the text supports the view that the family does show significant growth in the course of the play. Berkoff continued to use family as the primary chorus in East (1977), West (originally performed 1983), and Greek (1980). East is a loosely structured play composed of nineteen scenes with a minimal plot that introduces a scenario that is never fully pursued. At times it is reminiscent of Vaudevillian theatre: Cockney songs, comic sketches, and a mimed “silent movie” sequence. East’s structure contrasts with Metamorphosis which is much more plot oriented. In the former the characters are well-defined even though they represent certain working-class types: the angry young man; the used and abused girlfriend; the racist, working class father; and the disillusioned mother. Berkoff used this type of close-knit, character-oriented chorus through West and Greek, his next two original plays. West featured Les and Mike’s gang who serve as the chorus, even though the entire cast is to remain on stage for the entire show. The audience watch the play through two choruses in West: the gang as one chorus within the storyline, and then outside the story the entire ensemble serves as another chorus. The final small cast chorus-oriented play to be discussed is Greek. Greek is a liberal adaptation of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex set in the east-end of London. Berkoff uses the Oedipus myth as a broad outline for his own play. Berkoff produced the play with only a table and four chairs, saying “The family act as a chorus for all other characters and environments.” He claims that he, “ransacked the entire legend,” to create an environment, “full of riots, filth, decay, bombings, football mania, mobs at the palace gate, plague madness and post-pub depression” (The Theatre of Steven Berkoff 139). Decadence (1981), The Tell-Tale Heart (1983), Lunch (first performed 1983), Actor (1984), Harry’s Christmas (1985), Dog (1993), and Massage (first performed 1997), are one and two person plays composed of spoken internal monologues, asides, and stream of conscience dialogue. In lieu of a formal chorus, Berkoff substitutes a device in which characters speak their internal monologue aloud. This convention serves some of the same dramatic functions as a chorus: asks questions of the main characters; comments on the action; and acts as their conscience. In Lunch and Decadence, as in the larger cast Kvetch, the characters reveal their thoughts -- usually dealing with insecurity, loneliness or inadequacy -- before conversing in polite, public terms. In Lunch, a lonely man and woman size each other up on a bench at the seashore. They speak their interior monologues as asides, revealing themselves before speaking to the other:

(Collected Plays I 219) Insecurities are like a chorus of furies, swirling in their heads, as if it were a minimalist version of The Trial, stripped down to only words. These plays have bastardized choral elements that reflect a social and psychological framework; and, dictate the physical pace and rhythm. In Actor, Berkoff, inspired by a Marcel Marceau sketch, walked in place through the entire monologue, “as the actor walks through his life watching it slowly disintegrate” (Collected Plays II 229). Speaking in fragmented sentences, the “Actor” alternates between speaking to invisible others and editorializing to himself. His own thoughts, serving as the chorus, dictate the pace of his walk, as the rhythm of the speech increases, so does his movement.

The chorus in the one-man shows manifest itself as fear, insecurity, and loneliness in Actor (1984) and Harry’s Christmas (1985) and, in Dog, as the hostility and environment represented by Roy; who is in turn an extension of the Man's psyche and environment. Berkoff sometimes uses two characters played by the same actor, as in Dog, or two sides of a single character (the conscience and subconscience; or, the exterior facade and the internal truth), to form a chorus in the one-person shows. This chorus helps to establish a physical rhythm, as in the case of Actor and Dog and the larger social framework. His chorus' clarify and comment upon the main character through rhythm and dialogue. Functionally, Berkoff uses a chorus in his one-man shows to reduce the actor's need to naturalistically communicate their character's subconscience. Instead, the words do the work, and if well-acted, allow the actor a tour-de-force by alternating viewpoints, and, in some case, characters. Berkoff primarily uses a chorus as part of his directing aesthetic, yet he also considers a chorus, in literary terms, as a specific mouthpiece for the playwright. In small-cast shows especially, there are often individual characters who communicate the subtext and clarify the author’s message. In his adaptation of The Fall of the House of Usher (performed 1975; published 1977), Berkoff explains that Poe communicates directly through Usher:

Berkoff interprets the play as a living environment, everything -- including the house itself -- is sentient: “A tale of the impossible . . . A house with its own soul. A death. A resurrection. A moor’s pestilential environment. A house that outwardly manifests the crumbling nature of Roderick’s inner decay” (37). In a sense, there are two choruses mirroring each other: Poe’s literary chorus expressed through the tormented Usher, and Berkoff’s presentational style that uses the entire three person cast as a chorus. Berkoff’s use of the chorus in the Poe and Kafka adaptations also bridges the structural differences between a story and a play. As Berkoff’s writing jumps from episode to episode, it is the chorus that compensates for the lack of narrative. Berkoff's published adaptation of Usher is equal parts dialogue and interpretive blocking notes. Roderick Usher’s lines are descriptive, while the accompanying stage directions instruct the others to create friezes to reinforce the environment:

In the corresponding notes, Berkoff clarifies the exact function of this sequence:

This pattern continues throughout the play -- one actor will narrate while the others physically create the action. Visually, Berkoff composes his chorus as a painter might balance elements in a painting or a sculpture in a statue. Although classical Greek art is an influence, he is also inspired by fine art from other periods. Berkoff says his production of Messiah (2000) is in a “semi-religious devotional style, borrowing from the paintings of the great renaissance masters and from the sculpture of Michelangelo. The disciples form the backbone of the ensemble and, with protean ease, metamorphose from one group to another” (www.east-productions.demon.co.uk/ diary004.htm). In I am Hamlet (1989) he again acknowledges the influence of fine art on his work:

Further examples include his creation of human statues (tableau) in Agamemnon (1973); visual references to George Groetz in Usher (1974) and Tell-Tale Heart (1985), and Aubrey Beardsley in Salomé (1988). Berkoff modelled his interpretation of Titorelli in The Trial after Salvador Dali. Regardless of the many types of plays Berkoff has directed -- adaptation, original, traditional text, large cast, small cast, or one-person shows -- the chorus has consistently served as an antagonist. Berkoff maintains that his chorus are “neutral observers,” yet since his characters are mainly in conflict with their surroundings, it often makes the chorus, who serve as the environment, an antagonist. The rotting world, partly represented by the chorus, of East and West is a prison to Mike and Les; the same goes for Eddy in Greek. The choruses in the Poe adaptations envelop the characters creating psychological and spiritual decay, and, in Salomé, the chorus is the decadent court of Herod which contrasts to the martyrdom of Jokanaan. In Acapulco (1990), it serves as the banal cast and all that they, and the Rambo movies, represent. Hamlet’s environment is oppressive -- the rotting of Denmark; Coriolanus’ chorus sometime represents the fascist army and other times are plebeians in opposition to Coriolanus; and the Kafka plays' choruses serve as a world that torments and takes advantage of the protagonists. Throughout Berkoff’s oeuvre, the chorus serves theatrical, philosophical, and literary functions. Its use remained constant throughout his career, perhaps reinforced by Berkoff’s revivals and the repetitive nature of Berkoff’s career. The chorus is certainly one of the key components of Berkoff’s break from realism and creation of “total-theatre,” and is a propelling force in his work. The chorus is often proactive, serving to motivate the protagonist. In a sense, many of his characters’ objectives stem from the need to escape from their environment -- represented by a chorus. Berkoff’s chorus then has been a chorus of actors, a chorus of characters, and a chorus of ideas.

© Craig Rosen 2000 |