| home |

The

Falklands War Plays and Their Effect on Modern British

Drama Copyright © 2001 Melissa Green

In 1982, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, a small group of islands in the South Atlantic that had been under British rule. Great Britain wasted no time in protecting its territory; the fighting that ensued was known as The Falklands War. The brief conflict, which lasted only forty-one days, gave Great Britain a sense of national pride and made Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher a British hero. The Falklands War had a different effect altogether on modern British drama. The atrocities that took place, the politics of war, and the effect these events had on the British, the Argentines, and the Falkland Islanders disgusted several playwrights. They voiced their opinions on the theatrical stage and created political plays. Although seemingly dated, these plays were key elements in shaping views of The Falklands War through modern drama. The Falkland Islands, which sit three hundred miles off the coast of Argentina, have been under British sovereignty for over one hundred and fifty years. The islands have been an element of debate between the Argentine government and the British government for decades. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, debates concerning sovereignty proved unsuccessful for the Argentine government. They waited for the right moment to make their move to the Falklands. Months before the invasion, the Argentine government "tried to woo the islanders" (Barnett 25). The Argentines offered the Falkland Islanders a society different from the British, including a democratic government and different legal and education systems. The Argentines hoped that by offering changes, the Falkland Islanders would rebel against the British and be granted sovereignty. Yet, an overwhelming majority of Falkland Islanders did not wish to break free from Great Britain (Barnett 25-26).

There was no delay in confrontation, as debates began in England the day after Argentina's invasion. The House of Commons Digest stated that, "Parliament was recalled on a Saturday for the first time in more than twenty years on 3 April for an emergency debate" (4). Though the session began with an air of uncertainty on Great Britain's stance, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's persuasive speech swayed Parliament to officially declare war on Argentina. Members of the House engaged in "a thunderous 'hear, hear'" demanding "revenge wrapped thinly in the call for self-determination" (Barnett 46). Within days, British naval fleets were in the South Atlantic with air forces resting on their decks. The battles began less than a month later with the British sinking of the Argentine Belgrano, and the air and naval battles commenced. As the weather became colder, battles moved onto the rocky Falkland territory. After forty-one days, the Argentines raised the white flag and the British claimed victory at the stake of 255 British and 712 Argentine casualties.

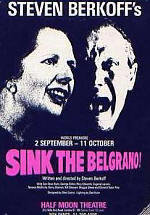

As the war began, Argentine propaganda began to affect the British public and made them wary of Thatcher's leadership. Rumors of heavy British casualties from Argentine media sparked questions of who was telling the truth, since Thatcher's government was withholding specific details from the general public (Thatcher 233). In The Iron Lady, Hugo Young stated that Thatcher's strict policies during the war affected her character, "[Thatcher's] reputation began to suffer in what had always been thought its strongest aspect: her guileless passion, so different from most other politicians, for telling the British people the truth" (279). Despite the general public's doubt of her concern towards British troops, Thatcher herself was completely consumed with the issue thinking "of nothing but the number of lives being lost in the war" (L. Hughes 120). Even the government was somewhat wary of her strength during wartime. Enoch Powell MP, House of Commons said during the April 3rd debate, "The Prime Minister, shortly after she came into office, received a soubriquet as the 'Iron Lady'... In the next week or two this House, the nation and the Right Hon. Lady will learn of what metal she is made" (11). As the war pressed on, Thatcher felt that "the outcome now lay in the hands of our soldiers on the Falklands, not with the politicians," while the country and Parliament were waiting for her next move and show of power (234). Thatcher formed a War Cabinet, and from London they placed all the orders for strikes against the Argentine forces. On June 14, 1982, Thatcher's "Falklands Guarantee...ended in great victory, eight thousand miles from home, it made her position unassailable, both in the party and in the country. It guaranteed her what was not previously assured: a second term in office" (Young 258). In the aftermath, Great Britain showed that it really was a "united" kingdom, "revealed by [Thatcher's] claim that she had put the 'Great' back into Britain" (Barnett 87). Though Thatcher had proved herself a strong leader, she and her politics stood as easy targets for playwright's scorn. This was demonstrated following The Falklands War when various British playwrights, angered and disturbed by the acts of the war, voiced their opinions theatrically. These political plays served as protests against the war with a public outlet in theatre. Thatcher's character was attacked through the playwrights' use of dramatic irony, "the sense of contradiction felt by spectators of a drama who see a character acting in ignorance of his condition" (Sedgewick 49). Thatcher's role and stance in The Falklands War was mocked by the play Sink the Belgrano by Steven Berkoff in the character of "Maggot Scratcher." Her policies and politics, "The Thatcher Effect," were points of further banter in such works as Arriverderci Millwall by Nick Perry and Restoration by Edward Bond. These playwrights' views of The Falklands War supported "their sense of crisis on the use of political violence...whether directed violence can resolve the crisis...[and] might reestablish the distinction between legitimate and illegitimate violence" (Dahl 9). One of the most vocal of The Falklands War playwrights is Steven Berkoff. Though three of his plays seem to focus on his detest of Margaret Thatcher, Greek, Decadence, and Sink the Belgrano, the latter work centers more on Thatcher's role in The Falklands War. The play deals with the first month of the war leading up to the sinking of the Argentine destroyer Belgrano by the British nuclear submarine HMS Conqueror. A chorus similar to ones in Greek plays sets up the story, while scenes featuring the Prime Minister and her War Cabinet, the sailors on the HMS Conqueror and the English public re-enact the days prior to battle. Tony Dunn summarized the play by saying that "Berkoff's 90 minute piece indicts the chauvinism of the British working class, reduces the War Cabinet to a comic threesome of Maggot, Pimp and Nit, and choreographs the drilling and disciplining of a submarine crew" (32). Berkoff used a variety of means to express his reactions to The Falklands War. His use of metaphors expressed his view and opinions of the war. The most apparent in Sink the Belgrano are the names of the key characters Maggot Scratcher, Pimp and Nit. The character of Maggot Scratcher most evidently represents that of Margaret Thatcher. Berkoff used no subtle means in this parallel, as characters throughout the play address Maggot as Prime Minister. In reference to the character of Maggot Scratcher, Monaghan stated, "Berkoff closes the always small gap that, in his opinion, exists between the grotesque figure who dominates his play and the real woman who...sent hundreds of Argentinians to their deaths without, it would seem, a moment's regret" (69). Maggot goes on to introduce her fictional cohorts in Sink the Belgrano using their non-fictional titles: "Where's my Foreign Secretary Pimp/ And get me my good faithful Nit/ Those two defenders of Tory strength" (158). Pimp and Nit represent Francis Pym, Foreign Minister, and John Nott, Minister of Defense. Pym and Nott were members of the War Cabinet and advised Thatcher throughout the war. The characters' names represented Berkoff's opinion of each of these government officials. Berkoff stated in retrospect that Sink the Belgrano is "the funniest play I have ever written and a caustic satire on the people who love to bask in the limelight of the world's adoring gaze" (Free Association 374). Sink the Belgrano also tells the story of the war from three different perspectives: the Prime Minister and government, the soldiers, and the English public. These point-of-views are represented through Berkoff's recommended staging with the stage divided into three areas representing the Prime Minister's house 10 Downing Street, the HMS Conqueror and an English pub area. In Berkoff's staging, 10 Downing Street represented the government's viewpoint, the submarine represented the soldiers at the front's viewpoint, and the pub area "represented the 'voice of England'" (Berkoff, Collected 143). Berkoff also took an eccentric approach in his playwriting through writing the entire play in verse. Berkoff stated, "Sink the Belgrano was written in verse and even by my modest standards was one of the best things I have done" (Free Association 373). Ned Chaillet described Berkoff's original use of language in the text as "a diatribe in punk-Shakespearean verse" (51). His use of verse along with modern adult language and slang was described at times as "simple, direct and often crude" (Monaghan 61). This technique helped relate his viewpoint to his audience in a popular English theatrical form, though some critics felt that the language could not support Berkoff's images (Dunn 33).

The focus of Berkoff's play, the sinking of an Argentine ship, was the starting point of the war. The Belgrano, guarded by two small ships, was located near the British Task Zone. The Task Zone was British occupied territory in the South Atlantic. There was an understanding that if the Argentine forces crossed the line into the zone, they were open targets. As the Belgrano continually approached the Task Zone, it turned around and continued on course. The British forces were unsure that the next time the ship approached it would turn around. After discussion, the War Cabinet gave orders from London to attack the Argentine vessel. In Iron Britannia, Anthony Barnett stated that the British "sank the General Belgrano quite illegally, which unleashed the real fighting war" (24). Berkoff purpose in writing the play was to voice his view on the illegal sinking of the Belgrano. He stated, "It is apparent to everyone that the sinking of the Belgrano was a very dubious affair and led to the severe attacks on the British Fleet and subsequent huge loss of life. How many people realize that before that calculated piece of sabotage not one British soldier had died!" (Free Association 146). Berkoff's personal response to the attack produced Sink the Belgrano as his voice of protest. Sink the Belgrano was different from prior political drama in its cynical and dark look at a situation, in this case The Falklands War. Nick Perry's approach of Arriverderci Millwall was one of parallels. He directly and indirectly compares The Falklands War to that of England's national pastime of football, known in America as soccer. The play follows the story of Billy, a South Londoner and supporter of a local football team Millwall. He is a lower class street vendor who leads a rough lifestyle. His brother, Bobby, visits on the eve of his marriage to ask Billy if he would care for his wife while he is gone to war. Then, the brothers' lives parallel throughout the wartime with both men fighting and losing their own battles respectively. Arriverderci Millwall presented several elements that the average Englishman could relate to, placing Perry's statement on a universal level of understanding. Football is a subject that most Englishmen can relate to. Perry's mixture of sport and politics is the most prominent theme seen in the play. A key speech in the text collates Billy's fictional account of a football match along with non-fictional accounts of the special session of Parliament held on April 3, 1982 declaring war on Argentina. Billy tells of watching the European Cup Final on television between Aston Villa, an English team, and Real Madrid. An Aston Villa player scored the game-winning goal only to be received by Madrid fans cheering 'Argentina, Argentina.' Billy was angered by the Madrid fans reaction, only to feel patriotism when Aston Villa fans sang 'Rule Britannia' in response. Intermingled through Billy's story, the speaker in the House of Commons calls for English unity in urging the government to declare war on Argentina. David Monaghan, in reference to Arriverderci Millwall, stated, "Nick Perry goes on to a broader assessment of the connection between Britain's military aggression against Argentina and the patriotic fervour with which the public responded to the outbreak of The Falklands War" (106). Both the fictional and non-fictional accounts Perry created in this scene call for loyalty and unity to Great Britain. The brothers communicate continually during Bobby's time at sea. When Bobby sees the war will not end as soon as he predicted, he sends Billy his tickets to the World Cup in Spain. Billy's trip to Spain is similar to that of Bobby's trip to The Falklands. Perry correlated the Spanish opponent in the football match to that of Argentina and the war. Monaghan explained, "Their enemy, literally the Spanish, is transformed...into the Argentines on the grounds that 'a spic is a spic'" (107). The trip to Spain proves to be a downfall for Billy, as the trip the Falklands does for Bobby in claiming his life. Arriverderci Millwall is occupied with violence. Mary Karen Dahl explained, "Violence conditions the human environment and human interactions" (1). Violence in Perry's created environment takes the form of war, football and street life. In war, death is an inevitable consequence. Bobby dies at sea during the bombing of his vessel. It is a gruesome and agonizing death described by Bobby's ghost: "we met our doom in burning water:/ I tasted fire, I tasted sea salt,/ I heard the screams of my companions,/ cruel screams; and - in a dream - / I heard my own voice screaming with them/" (53). After Bobby's death, he appears in several scenes to his brother in spirit form. Through the character of Bobby's ghost, Perry relates patriotism and the ultimate price of war to the audience. The violence of war also transforms Billy with a sense of national pride and responsibility. Dahl stated, "Violence transforms the victim in terms of its value to the community at large. No other action could have so changed it. We have arrived at the singular paradox of violence: the act of destruction as an act of salvation" (5). English football also narrated another form of violence. The sport itself can be rough, through the fighting for the ball and fierce competition between the competitors on the field. The football players, similar to soldiers in The Falklands War, fight to protect what is theirs from their opponents. Yet off the field and in the stands, it is often the fans that get out of hand. Their undying and often aggressive support of their teams can lead to violence. Perry again displayed another use of parallel in the text between these patriotic and fanatic means, as well as the meaning of loyalty. Billy tells a story about his father taking him to a football match as a child. They arrived early to find fans of the opposing team waiting for the gates to open. Billy states that he ultimately spent the time before the game watching the opposing fans beat his father up while he stood shocked and silent. Inside at the game, Billy recalls "wanting to tell him [his father] to wipe the blood off his mouth. But he didn't. And he never said a word, not then or ever. It was like it never happened. Except for the blood on his mouth and the piss and the shit on his coat" (Perry 37). Loyalty, in this case, is an excuse for an occasion to use violence. Billy and his friends exist in the Southern London street lifestyle. They are all street vendors, often selling stolen or damaged merchandise for profit. They have a violent nature in dealing with each other, their family and anyone who poses a threat to their way of life. Their only solace is in Millwall football and their religious attendance of Mass once a week. To them, South London is the only place to be: "London's always first. And first is first, second's nowhere. London talks, England walks. South London to be exact" (Perry 5). Billy and his friends face a battle daily in these rough neighborhoods where gangs, mostly aggressive supporters of other football teams, are ardent in the viewpoints and ready to fight with no thought. In Billy's lifestyle, violence is a way of life. Yet his life becomes even more violent when his brother dies in combat, proving that violence does indeed breed violence. Arriverderci Millwall, an underground work by the unknown Perry, premiered in 1985 at the Albany Empire Theatre in Deptford, a small borough of London. Perry and the play were well received, but not validated until a group of Cambridge University students presented the play at the Edinburgh Festival. Perry was honored with the Samuel Beckett Award for first stage play in 1985. The play became extremely popular, and was picked up by Faber and Faber, Ltd. for publication. In 1990, the play was re-worked into a screenplay for the BBC giving Arriverderci Millwall "significant exposure for it to be considered a genuine threat to Thatcherism" (Monaghan 100). The play was a work that brought South London life to the mainstream stage, and relayed a feeling that The Falklands War affected all social classes. Though Arriverderci Millwall is completely fictional in story line, there are some elements within the play that have historical parallels. Bobby's entry into The Falklands War relates the patriotism many soldiers had towards the cause, while Billy's uncertainty of why his brother should go is a similar question asked by the general English public during wartime (Barnett 87). Bobby dies during the sinking of the fictional destroyer HMS Indestructable, which through Perry's description sounds similar to the non-fictional English destroyers HMS Coventry and HMS Sheffield also sunk in battle (45). Another small and interesting historical parallel is within the story is that the World Cup was held in Spain in 1982 as in the play. Through Perry's use of parallelism throughout Arriverderci Millwall, a different story of The Falklands War emerged finding a "way of prying open the apparent monolith of Thatcherite ideology in order to expose its inherent flaws" (Monaghan 100). The use of a lower class perspective accentuated understanding of that class's lifestyle. Suprisingly, Perry's use of the lower class viewpoint of the war revealed an opinion similar to the rest of the nation. Barnett stated, "There seemed to be no class divisions over the Falklands. Support was only widespread, it cut across political and social divisions" (88). The Falklands War shaped Arriverderci Millwall by combining the war and football to illustrate a clearer understanding of what a soldier's family was going through. Bond's text took a less direct approach to The Falklands War. The play had no direct mention of the war, just insinuation paralleling the politics and relationship between the government and the soldiers. Restoration is set in eighteenth-century England, though the time and setting is really not important in understanding the piece as a whole. Due to his bankruptcy, Lord Are is forced into marrying to a woman of a wealthy background. One morning he decides that despite his own poverty, he does not want to marry the woman and instead kills her. To keep his good name, he seeks to blame the murder on his faithful footman, Bob. Bob's loyalty to his master blinds him from seeing his own innocence, ultimately spelling his own demise. Bond's theatre, in this case Restoration, alludes his own political thinking. Its purpose was not to present propaganda, but to present information to let the audience form an educated opinion (Bond, Hidden 23). The play's Restoration period style comedy surface is the first element in shaping that opinion. "Bond," Stephen Weeks stated, "has long been interested in reexamining period styles and texts from a contemporary political perspective" (241). The first act proves light-hearted and comedic, while the second act reveals a more serious issue and tone. Lord Are's relationship with his fiancée and Bob's silly and ignorant character in the first act seem frivolous, setting the audience up for an evening of laughs. Bond twisted Restoration in the second act to show that what is shown on the surface is not as happy as it seems. In reference to the play, Jenny Spencer wrote, "As a comedy of manners in Part One gives way to the comedy of tears in Part Two, the audience's complicit, self-conscious laughter makes way for equally complicit, self-conscious suspense" (178). This tactic used by Bond parallels the thought that there was more to The Falklands War than was revealed by the government (Barnett 95-98). An issue Bond addressed throughout Restoration is the representation and treatment of social classes. In the text Bond showed "the respectable world and its apparatus of justice and hypocrisy" (G. Hughes 78). This representation could also signify Thatcher's politics of The Falklands War. Bob, the servant, is punished for his master's mistake. Bob's punishment, in this case, is his own death. These events are very similar to the soldiers' in The Falklands War in the sinking of the Belgrano. Margaret Thatcher, being the master in this case, made the decision to sink the Argentine vessel outside of the Task Zone. This British attack was the beginning of air and naval battles leading to 255 British soldiers' deaths (Reginald 77-78). In a later scene, the commoner Bob's downfall produced innocence for upper class Lord Are. Likewise after the high number of casualties during the short war, Thatcher became a hero and was rewarded politically. In reality, the soldiers, as servants, were only obeying the master's commands. Though not given a specific name, Bond used the element of war within the text at various times. Bob's girlfriend Rose sings a song asking, "Do the troops shoot/ To kill your stomach but not your head? They shoot to kill/ You drop down dead" (99). Another character within the play, Gabriel the blind swineherd, serves a small but pivotal role in the understanding of the politics of war. Gabriel is the only character in the play with a true connection to war, where he lost his eyesight in battle. He stated, "People allus fuss over what they can't mend. The whole world up an' everyone slid off - thass jist a saucer of spilt milk" (62). Gabriel's speech supports Bond's thinking that the war was just another event feted by the government at huge British costs (Bond, Hidden 154-155). Bond's use of theatrical elements within the play allowed a greater element of understanding for the audience. His ease into the true subject of the play juxtaposed the audience and their first understanding of the play. By using colorful costuming and scenery in creating a drawing-room type comedy, Bond related his opinions to the audience simply. Bond also used the element of song within the text. These Brechtian-spirited songs disclosed the characters' true personality and visions. The songs' tone also caused many of the audience to shift their focus to the dark undercurrent within the play. One song, sung by most of the cast, revealed Bond's opinion of the war, "Into the trenches and into the blood/ Bellowing shouts of brotherhood! / They break their brothers' bones when they are told/ They think they walk in freedom? - they are sold/ To the butcher...Hurrah! For every Englishman is free/ Old England is the home of Liberty" (Restoration 77). Originally, the audience accepted what they saw and heard at face value. As the play progressed, Bond showed them the differences. Bond, being a very popular and widely produced playwright at the time, first presented Restoration at the Royal Court Theatre, London in July 1981. Early criticism of the play stated, "Not suprisingly, audiences enjoyed the play's first half, with its self-conscious parody of Restoration comedy, more thoroughly than the second, where conventions shift and take their toll" (Spencer 173). By the time Bond re-issued the text in 1988, the new edition did not perform at the Royal Court. Restoration was already in circuit throughout London's fringe theatres and around the world. Stephen Weeks said in a review of the re-issued text that "the play's rousing politics create an inescapable dissonance of message and ambiance... By juxtaposing a comedy of manners with his own brand of epic realism, he [Bond] moves by degrees into the special territory of his work: the analysis of systemic injustice under capitalism" (241-242). Both versions of this text are riddled with policies and politics leaving the audience asking the question "why?" in response to what Bond has presented them. The politics of Restoration, in this case the Thatcher era, are what shadowed Bond's underlying message about The Falklands War. Though this play does not directly discuss the Falklands War, the shaping of the text brought the message of protest out into the open. Bond wrote, "When a society is unjust there is no freedom: everyone is in a ghetto of poverty, fear, anger, insolence, sentimentality - a ghetto of danger. In this ghetto it is difficult to understand but easy to feel. And there comes a lethal cocktail of misunderstanding and emotion - and it is this that leads to violence, to robbery and even to murder" (Hidden 74). Restoration contained a bit of all of these elements suggesting the war was unnecessary. Bond's use of violence and cruel humor in Restoration could be compared to Brecht or Artaud. These ideas, as seen in the play, are used by Bond to create his outlet of protest and to transform the audience's viewpoint of the matter. Bond's writing created a "rational theatre, dedicated to the creation of a rational society" (Cohn 68). In hopes of creating a rational society, Bond's response to The Falklands War is best said by one of his own characters, "Man is what he knows - or doesn't know/ The empty men reap death and sow/ Famine wherever they march/ But they do not own the earth" (Bond, Restoration 100). The Falklands War, though not well known worldwide, affected British history forever. Freedman wrote, "Episodes such as The Falklands War provide us with an insight into the nature of the moral sensibilities of a country like Britain at a time of crisis" (106). Great Britain showed its might as a military, as a government, and as a people. Freedman said in his preface, "The British Isles were not at risk during the conflict...At stake were the intangibles of national pride and international norms, and if they were satisfied in the end, it is hard to say whether this was worth the cost in the tangibles of human and material resources" (xi). In other words, the war was not a battle for independence but for dignity. The war proved that Great Britain had great military force. Thatcher felt that the war showed Britain's strength: "We had come to be seen by both friends and enemies as a nation which lacked the will and the capability to defend its interests in peace, let alone in war. Victory in the Falklands changed that. Everywhere I went after the war, Britain's name meant something more than it had" (173). British soldiers were seen as a military that could stand on its own in battle. The Falklands War victory allowed Great Britain to confirm its placement as a world superpower. The strength of the government was also validated during The Falklands War. Margaret Thatcher and her War Cabinet were a strong force to be reckoned with. The British Government's case with Argentina stated that, "the seizure of the islands at the start of April 1982 was a blatant breach of international law, which stresses the need for the peaceful resolution of international disputes and condemns unprovoked aggression" (Freedman 109). The War Cabinet held many debates within Parliament, and sought advice from ally countries such as The United States, Japan and Canada. All in all, the War Cabinet made their own decisions, and ultimately their "failure of diplomacy to prevent war resulted in a major boost for British international prestige" (Parsons 157). Other countries admired Great Britain's handling of the Falklands situation. A democratic monarchy prevailed in a modern war showing the Prime Minister's great influence on the country. Margaret Thatcher was greatly in favor after the war by bringing home a British victory. Freedman wrote:

All across the timeline in world drama, theatrical responses were made to wars. Historical and political war plays and criticism exist, but few of those have made their mark on modern drama. The Falklands War, though little known on the world history timeline, made a stronger mark on modern English drama than on world drama. The afore-mentioned plays, Sink the Belgrano, Arriverderci Millwall, and Restoration, all reflected an attitude of their time. These plays showed audiences the playwrights' opinions of the war and the people involved with it, as well as a look into 1980s Great Britain. They served as a form of protest against the war, and of protest against Thatcherite lifestyles at the time. Post World War I and World War II plays served as a model to theatre historians in understanding their era. Yet, little is known and said about The Falklands War plays. The war was small in scale compared to the World Wars, but to England and Argentina The Falklands War played an important part in shaping their history and society. Though no Argentines wrote plays about the war, there were English plays written telling stories for both sides of the battlefront. Not only are these plays entertaining, but they also gave artistic meaning and perspective to an otherwise completely political situation. The interesting point about these three works is that they all are against The Falklands War. That is a seemingly different response from the rest of the general public who supported the war. Their theatrical protests showed the soldiers whole-heartedly following commands made by the government. Many of these soldiers were blindly lead to their deaths. Though all the these playwrights, Steven Berkoff, Nick Perry, and Edward Bond, take different approaches in their opposition of the war, all show a viewpoint different from the general public. Ultimately, the point all of the playwrights made was that the war could have been prevented and lives could have been saved. It has been almost twenty years since

the Argentine forces first occupied the British ruled

Falkland Islands. The war opened the eyes of people

throughout the countries involved, as well as throughout

the world. Reginald and Elliot wrote, "The outbreak

of war in the Falklands puzzled many outside observers,

and sent others running to their gazetteers and atlases.

While scarcely idyllic, these islands were sufficiently

isolated from the world's cares that they were seemingly

immune to any but the most modest disruptions"

(131). The war also made the playwrights of Great Britain

aware of their country's situation, and allowed them to

create their own opinions through dramatic means. Though

British forces won the war, the issue of contention for

The Falklands still remains today. Until that question

can be answered in the future, the answer stands in

British sovereignty. The Falklands War plays endure to

tell the story of this war that shaped modern British

history, society and drama. Works Cited

|